Alan Seeger and The American Library in Paris

Excerpted from

A RENDEZVOUS WITH DEATH: ALAN SEEGER IN POETRY, AT WAR

With the death of his son, Charles Seeger’s full attention seemed to shift fully to extending the effect and memory of his life. By all examples, and like his wife, his public actions took precedence over whatever the nature might have been of his personal feeling. By late 1916, he was living in Paris and working for the India Rubber Products Company. He had conceived and enterprised the publication of Poems, followed by Diary and Letters, and was the softly aggressive facilitator of their production. An account was set up to receive royalties from the books at Farmers Loan and Trust on Hausseman Boulevard in Paris, and a letter to Scribner’s from Elsie Seeger indicated that with them they would be “able to do so much for Belloy-en-Santerre, & make the whole village beautiful.”

The Seegers’ greatest attention to the village where their son had died would come later, but when the war ended in 1918 Charles took the first steps in the creation of the third and most lasting version of an American library in Paris.

During the war, one of the most acute needs of American soldiers abroad was for books to read. As in Alan Seeger’s case, fighting war could be bursts of action amid days and weeks of boredom. Seeger was constantly reading books that would be sent to him from friends. It was multi-lingual and mostly intellectual reading as a supplement to his own writing. But most American men in Europe needed the same books they would be reading at home, and more of them than they would read in the course of their day to day lives in America. The American Library Association (ALA) had been formed in relation to the American Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876, and was designated by the U.S. government to administer library services to American troops at war, both at home and abroad.

It became a grass roots effort, derived from the staffs and patrons of 3,000 member libraries. By one account, it was able to generate more than 4 million books over the course of the war – 3 million of those from library patrons – and 10 million magazines. Most of them were distributed within the U.S. through 400 base libraries, with smaller branches in more than 2,000 hospitals and social agencies related to the military.

All ships and troop transports of the U.S. Navy carried small libraries, and approximately 50 tons of books were sent to Europe as cargo each month. More than I million books were distributed through a library facility in Paris administered by librarian and author Burton Stevenson. Though books were mailed to some soldiers individually at the rate of 1,000 each month, they were for the most part sent out not to where soldiers fought, but to more than 300 places where they would seek rest, recreation and medical care. In its request for contributions, the ALA made a point of suggesting that they did not need to be “goody good,” but those that these men would actually read. And the flow of books was also curated to develop an accessible reference library in mostly technical subjects that were relevant to the war and to its aftermath, among them aviation, forestry, infrastructure, engineering, mechanics and military science. They included books to help teach literacy, and for those performing at academic levels, and to prepare men for life after war, all published over a range of 40 languages. The motto of the service was “Give every man the book he needs when he wants it.” Its almost unspoken agenda was to convert a captive audience of millions of young Americans into lifetime readers.

At the end of the war, and with the departure of American troops over the following months, the future of the library operation in Paris became uncertain and vulnerable to the fate that had fallen upon two previous attempts to create a lasting American library in the city.

The first was the effort of Alexandre Vattemare, certainly one of the most interesting of Frenchmen of the early 19th century. As a child, he found an inborn skill for ventriloquism and voice mimicry, though, befitting his born status in society, he trained to become a surgeon as a young man. He did not succeed in the effort, by some accounts in part because he enjoyed giving voice to his training cadavers or to those still in their vaults. He then performed as a ventriloquist and mimic of people and sounds all over Europe and in the presence of royalty, evolving into a playwright who produced historical drama in which he would perform each part in a different voice. Financial success eventually led to him to philanthropy and international advocacy. He was able, as an example, to have placed before the U.S. Congress a proposal for international standards in weights and measures. But he would be defined by his promotion of a new idea: the books of the world, thus the culture and information they contained, should be exchanged internationally through the world’s libraries.

Thus, as an example, Vattemare was found speaking to the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond one evening in November 1848. He had been succeeding in his effort in Europe and Russia for some years, and he had first come to America at the urging of the Marquis de Lafayette nine years earlier. In Richmond, as elsewhere, he was well received, in this case by Virginia Governor William Smith.

"As has been simply, yet truly said by Mr. Vattemare, the man who presents even a glass of water to another, with a smiling face, and in spirit of kindness, wins favor: so this system of international exchanges must produce an interchange of good feelings amongst the nations of the earth. Heretofore, the system has depended upon the life of the originator, but it is hoped that he has succeeded in establishing it so firmly, that it may survive him if he should be taken from us, an event which we all should form our hearts deplore, and which we trust may be postponed for many, many years. "

Vattermare’s effort to open an American library in the Paris city hall was begun in that year, and by 1855 the city had appropriated the funds to place American books in 32 building alcoves. The library contained 10,000 books, and a campaign within America sought further contributions that would reflect the differing histories and influences of each state. It became a project of academics and social leaders in both countries, accompanied by a perceived opening up to the English language and American culture within France.

Then, at some point or points in the following decades, the library disappeared – twice. Writing in 1909, William Steell, the American playwright and author, and eventual editor of the Paris edition of the New York Herald, suggested that “this collection of Americana has vanished as completely as the vast library of Alexandria, founded by the Egyptian Ptolemys.”

Alexandre Vattemare died in 1864, credited, among many other accomplishments, with an integral role in the founding of free libraries in Europe and America, and in the creation of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. The international exchanges that he had developed in life would continue, though without the energy of his support. In January 1871, a result of the Franco-Prussian war was civil unrest in Paris and the destruction by fire of the city hall. Realization that the library had been lost did not seem to come about until the reconstruction of the building commenced. In truth, it may have been the case that the library was of little interest to the people of Paris, especially after Vattemare’s death. It turned out, however, that the collection of American books had been of greater interest to the large American expatriate community of the Passy neighborhood of the city, and, after considerable negotiation in 1867, it was moved without public attention to the Passy city hall.

At the time of reconstruction of the Paris building, renovation of the Passy building was begun and the library was moved to a warehouse. Paris now demanded the return of the books for its new city hall. Passy agreed, Steell reported, and it would later be able to show receipts indicating that they had been removed from the warehouse, but they would never arrive back in Paris. Despite at least one subsequent search in 1898, the books were never found. Other narratives say simply that the books simply were continuously passed on to the regional libraries of France in small lots, until there were none left to be found. An attempt to recreate the library in the Paris Hôtel de Ville, according to Steell, would include only books printed since 1870.

Another attempt at an American library was undertaken by Theodore Roosevelt’s ambassador to France, Robert S. McCormick, in 1905, but came to nothing. The war would be the spur, and in October 1919, the American Library Association took the first steps to convert the Paris distribution center into a permanent facility at 10 rue de l’Elysée, with a view to the gardens of the Elysée Palace. Though he would be leaving, Burton Stevenson agreed to put an administration in place for the following year if its expenses could be guaranteed. It would include a professional librarian with 15,000 books, soon to be supplemented by an American Chamber of Commerce of Paris library collection of 40 years, and a plan to bring it up to date. It was still in use by lingering soldiers, but had been opened to civilians and used increasingly as a reference library by French citizens. The operating budget would be 150,000 francs annually, and Stevenson said that if he could not assure its future in Paris he would bring it back to the United States intact.

In November, Charles Seeger, Sr. wrote to the American Library Fund to offer 50,000 francs toward an endowment in his son’s name. The amount was constituted of accrued royalties from Poems and Letters and Diary. He and his wife had been seeking a memorial for Alan that would be both useful and in keeping with his character and belief. “Our son loved books and he loved Paris as well. We cannot think of any better employment for the sums derived from his verse and his prose than to help, even though in a small way, to found a library, which is destined to be the home for lovers of English books in the city in which he lived and to which he was devoted.”

The contribution would start with 35,000 francs, then 15,000 to be provided in 1920, and the pledge of further support if possible. Its only conditions were that it be called the “Alan Seeger Endowment,” that it become a permanent or capital fund of the library, and that earned interest be used for expansion into departments of poetry, the classics and belles lettres. The secretary of the fund responded with gratitude and agreement to the terms. “This library,” he wrote, “brought here for our soldiers, will always remain a living memorial to those of our land who fought and died on the fields of France. It is therefore singularly fitting that its first considerable endowment should commemorate one who is preeminently the spokesman of his generation of ardent and generous youth.”

Charles, who was now the Paris vice-president of the United States Rubber Export Company, was made chairman of the organizing committee, accompanied by other American businessmen and those involved in postwar finance and reconstruction. Their work was seen by some in France as an instructive example of American enterprise and openness, and a reference source for the mechanics of that spirit. In the international community, it was a vehicle for cooperation, especially between the U.S., France and Great Britain, during a time of postwar stress as they worked to settle leftover issues of the war. As it was gaining its new footing in 1920, the vast American distribution facility transforming to a public library did not go unnoticed in other nations that were finally coming out of the haze of war. The concept of free public libraries was new to Europe, and the most visible of attempts to adopt the American model shown in the Paris library came in a law passed by the national assembly of Czecho-Slovakia that each city, village and town contain a free library. Similar legislation was passed in Poland.

In France, the French-American experience of the war had contributed to a new interest in American literature, and information about their recent ally, on the part of many French. Though French bookstores saw increasing displays of American classics in both languages, exchange rates had made imported books prohibitively expensive. The Carnegie Foundation for International Peace would eventually create collections of American books for donation to educational institutions, but for those French who could read English the American Library was perhaps the most useful resource. The New York Times reported that it received 500 daily visitors, one-third of them French citizens. “They seem to find it especially valuable as a working library, and, although a good many take out books on cards for home reading – a system hitherto unknown to French readers – the main use which the large French patronage makes of the library is for working purposes.”

Depending on their status in the library’s development, different entities paid varying membership fees, ranging down from 5,000 francs annually to 20 francs for subscribers with borrowing privilege. Use of the reference and reading rooms was free. Eventually it would be able to attain the funding of $500,000 that would put it on a permanent foundation. Its dedication took place on December 19, 1920 with the placement of a plaque in honor of the Americans killed in the Foreign Legion.

Pictured above: The Monument to the American Volunteers Fallen for France at the Place des États-Unis, Paris, is topped by a statue in the likeness of poet Alan Seeger, who wrote about the war in poetry and essay, and would be considered a Hero of France into the 21st century. It is not as well known that the royalties from his posthumous books would help to fund the founding of the American Library in Paris in 1920.

Learn More

The American Library in Paris, which celebrates its centennial year in 2020, was founded in part with royalties earned from the 1916 and 1917 books of the American poet Alan Seeger, Poems and Letters and Diary. Seeger loved Paris and France, and had joined the French Foreign Legion after the German invasion of the country in 1914. He died at Belloy-en-Santerre in the Battle of the Somme on July 4, 1914.

Seeger's father, Charles, was the library's founding chairman. He would help to create an institution that would influence the develop-ment of public libraries in postwar Europe, give depth to the relationship between the United States and France, and steer a course of both co-existence with and subterfuge against the Nazi occupation of Paris.

Though 100 years old in 2020, the actual history of American libraries in Paris stretches back to the mid-1800s.

10 rue de l’Élysée

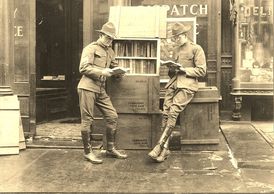

The first location during World War I at 10 rue de l’Élysée. At the time, the library held 25,000 volumes.

Reference Room 1920

The library became a source of knowledge about America, a recent ally in war. And it was a source of postwar technical and avocational information. The concept of open access to library shelves was new to Europe.

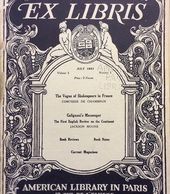

Publication Ex Libris

The first edition of the library's own publication, Ex Libris, in July 1923.

Dorothy Reeder

Dorothy Reeder's career began at the Library of Congress in Washington and she became director of the American Library in Paris in 1937. With the German occupation of Paris in 1940, she was credited with keeping the library open, and continuing hidden service to the Jews of Paris.

Current Home

In 1964, the library moved to its current location at 10 rue du Général Camou.

A Biography of Alan Seeger

A Rendezvous with Death: Alan Seeger in Poetry, at War was introduced in an author event at the American Library in Paris in June 2017.

Copyright © 2026Chris Dickon - All Rights Reserved.