The Situation at the Margraten American Cemetery - 2026

Reporting

In November 2025, the American Battle Monuments Commission removed an educational panel from the Visitor’s Center of the Margraten American Cemetery in the Netherlands. The removal was controversial and continues to be a point of conflict between the ABMC, African American historians and advocacy groups and Dutch citizens of the Limburg Province of the Netherlands.

The two panels briefly recounted African American history in relation to the cemetery through a profile of one of its 172 African American burials, George H. Pruitt, and the initial digging and construction of the cemetery by the African American 960th Quartermaster Service Company.

The panels were placed at Margraten in 2024 1 as a result of the work of the Black Liberators Project, an effort of the Dutch people. 2 They were removed without public notice after a private discussion among officials of the ABMC as a response to a presidential Executive Order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” 3

In December of 2025, The Jewish Telegraphic Agency obtained related emails within the ABMC under the Freedom of Information Act 4 The emails covered an effort to remove reference to the racial history of the cemetery pre-emptively as an indirect response to the Executive Order “to avoid raising any ire of the administration.” 5 The panel most in contention was related to the construction of the cemetery by the African American Quartermaster Company over an historically brutal European winter, amid the press of dead of the final battles of the European war, including the nearby Battle of the Bulge.

The panel’s narrative gave the basic information of that event. In the aftermath of its removal, it was prominently described as containing “errors of fact and omission that needed correcting.” 6

This is the text of the panel, footnotes related to facts are added.

African American Servicemembers in WWII: Fighting on Two Fronts

During World War II, the U.S. military followed a strict policy of segregation. 7 Despite the ongoing fight for civil rights at home during an era of racist policies, more than a million African Americans 8 answered their nation's call enlisting in every branch of the military.9

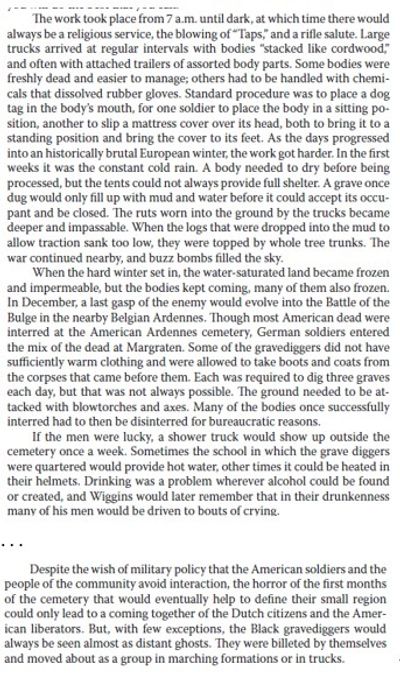

Although limited to serving primarily in labor and support positions, 10 Black service members regularly faced the horrors of war. In the fall of 1944, the 960th Quartermaster Service Company (QMSC)-composed primarily of African Americans - arrived in Margraten to dig graves at the newly created cemetery. 11 First Lieutenant Jefferson Wiggins of the 960th QMSC recounted the suffering of service members under his command who "cried when they were digging the graves... they were just completely traumatized." 12

President Harry S. Truman finally ordered the US military to desegregate in 1948. 13 However, African Americans' fight for civil rights was far from over. Many Black soldiers, including Wiggins, returned home to become leaders in the Civil Rights movement. 14 The achievements of African American service members in WWII served as a powerful claim for equality then and now.

In January 2026, the ABMC installed a replacement panel, which noted the work of African American soldiers and Dutch citizens, without elaboration. 15

Reporting on the changes at Margraten has been international, mostly reflecting unhappiness by Americans and Dutch, and members of Dutch Government. 16

Opinion

The new and current panel about the creation of Margraten says only about the African American role: “much of the work of digging the graves and burying the dead [was] conducted by African American soldiers . . ."

A fuller description of that work is synthesized, at left, from James Shomon’s Crosses in the Wind. 17

James Shomon was a white commander of Black troops. Though Crosses in the Wind was a narrative of heroic work by his gravediggers, it included this description of them in the stereotypes of the time of its publication in 1947:

"They looked and looked; then suddenly a few made a break for the latrine. Back they came, however, and they looked again. I heard one mutter, "Gruesome ain't it? Sho' is gruesome. Ah can't standing working hyar. Ah's gonna dig graves. Yassuh, give me a shovel. You kin handle him. Ah's gonna dig graves." 18

The question of the proper role of the US military in relation to the problem of American racial discrimination has been asked and answered many times in the last 100 years: Is its sole responsibility only to the defense of the nation as efficiently as that can take place? Or, does it have an added responsibility to ensure that American ideals of racial and social equality are at the foundation of that defense? Can the blending of the two make American defense more or less effective?

The time of World War I was a time of an epidemic of extrajudicial lynchings of Black people and the rise of the KKK, largely prompted by the film “Birth of a Nation,” which had been screened inside the White House of President Woodrow Wilson. 19 With the advent of war, and the consideration of who should fight it, Wilson’s Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, asserted that the military would not be an agent of social change. It could not “undertake at this time to settle the so-called race question.” 20

When a draft law was enacted in May 1917, it yielded 26 percent of the eligible white population, but 31 percent of the eligible Black population. 21 Black enlistees were fully segregated within non-combat operations. And, as would occur in World War II, the US military also attempted to impose segregation within the European societies in which it operated. 22

By the onset of American participation in World War II nothing had changed. Efforts to bring African Americans into equality in fighting forces were discussed in back channels, but ultimately dismissed by Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall as “tantamount to solving a social problem which has perplexed the American people throughout the history of this nation. The army cannot accomplish such a solution, and should not be charged with the undertaking.” 23

Jim Crow was in full force in the United States at the time, and it would be exported through military segregation practices to American forces and the societies of Europe in which they fought. Efforts at the higher levels by some to alleviate those restrictions would be met at even higher levels with resistance.

As an example, an effort was made in December 1943 by Gen. John C.H. Lee, who supported limited forms of integration, to combine certain Black and white combat forces. It was met by Brig. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Walter B. Smith’s warning to Eisenhower that the allowance of integration of fighting forces as the war became more difficult might seem to be hypocritical and desperate, and was “the most dangerous thing I had ever seen in regard to negro [sic] relations.

I have talked with Lee about it, and he can’t see this at all. He believes that it is right that colored and white soldiers should be mixed in the same company. With this belief I don’t argue, but the War Department policy is different.” 24

Eisenhower, though accepted as brilliant in his conduct of the war, seemed never able to solve the problems presented by the application military racial policy in the conduct of the war, and acceded to Smith’s warning. Eisenhower’s voice in racial matters extended throughout the war, and even to England, where he warned against the racial naiveté of the people, especially British women.

“They know nothing at all about the conventions and habits of polite society that

have been developed in the U.S. in order to preserve a segregation in social activity

without making the matter one of official or public notice.” 25

In 1946, President Harry Truman convened a President’s Commission on Civil Rights, and issued an Executive Order in 1948 to end segregation in American armed forces. Over time, it was considered to have been effective in bringing about an integrated military force, and in some minds as an example of benefit to the larger society.

In 1997, posthumous, and one living recipient, Medals of Honor were given to African Americans of World War II who had been precluded from the honor by policy against it. A previous posthumous Medal of Honor to an African American of World War I had been awarded in 1991, 73 years after the death of its recipient.

In the matter of the Margraten American Cemetery:

When African American troops arrived in the liberation of the Limburg Province of the Netherlands in 1944, most Dutch had little or no experience with Black people. Following military policy, American Blacks and Dutch whites were strongly urged to avoid each other, but the Dutch had the example of the visible and active segregation of Black and white American soldiers as how Blacks were to be treated and considered. In the remarkable struggle through a brutal winter and the last large battles of the war to lay out and dig a cemetery, then to bury an initial population of 18,000 dead, the Dutch people watched it all from a distance until, in the most dire moments of the cemetery’s creation, they joined with the African American gravediggers to get the job done. They learned something about each other, and it was not forgotten in the community’s memory.

After the turn of the 21st century, the people, leaders and historians of Limburg began to investigate the origins of the large cemetery in their midst, now with 8,200 American dead and 1,700 Missing in Action memorialized. My co-author for the book Dutch Children of African American Liberators, Mieke Kirkels, was a leader in that movement as an author and Public Historian in the Netherlands. Eventually the story of the African American gravediggers emerged into the understanding of that history in the larger context of social equality.

Then the research and remembrance of that history led to the discovery of 172 African American soldiers buried in the cemetery, and the desire to know more about them and what their experiences had been. A disregard for all residents of the cemetery - Black, white, Jewish and others - was not implied; all of its individual graves are adopted by regional families for attention, maintenance and, in some cases, relationships with their American families.

The interest in the stories of all African Americans who had participated in the Liberation of the Netherlands has extended into the present day. 26 In 2024, with the co-operation of the ABMC and the help of the American Ambassador to the Netherlands, the people of Limburg succeeded in adding the display to the cemetery’s visitor center about that history from their feeling, perspective and understanding - which was that these people who had arrived among them to liberate their country and help in its rehabilitation had been doing so under the further strains of historic American racism – yet they had given so much.

In 2025, one of many similar Executive Orders from President Donald Trump directed a reduction of the telling of African American history within organizations of the federal government. Though it had not been directed to respond to the order, the ABMC pre-emptively began to scrub its website of most racial history, and to remove the fuller story of the African American gravediggers from the cemetery’s informational material, thus from the Limburg community which had worked to have it placed there as part of its historic care for the American cemetery and those who were buried and memorialized within it. An alternative, suggested in the emails, was removal of the material to storage until the end of the current presidential administration in 2029.

In a statement about the removal, the ABMC stated that “The Netherlands American Cemetery, with its singular mission to honor those who fell in combat and are buried and memorialized there, is not the appropriate venue for interpreting or debating broader societal issues, however real and significant those issues were and are.” 27

Within a century’s time, the language and intent remained similar to it was not the role of the US military to “undertake at this time to settle the so-called race question” in 1917. And “as the most dangerous thing I had ever seen in regard to negro [sic] relations,” in 1943. And "The army cannot accomplish such a solution ."

A personal observation:

I have been to the Margraten American Cemetery twice in research for two books related in part to American burials in the Netherlands and the biracial children of African American soldiers in World War II. And I’ve formed brief or extended, personal or email relationships with some of the principals in this story.

The book about American burials, and another about Americans who fought with foreign forces in both World Wars, took me in person to American and British military cemeteries in England, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, and in research to war cemeteries worldwide. All of them were built out of the crucibles of wars that were personally experienced and felt, or well-remembered within families of the regions in which they were fought. I have sat with citizens of these countries on American Memorial Day as they have talked about their caring for a given cemetery and the people within, sometimes in tears driven by good beer.

I’ve been to Margraten on Memorial Day as an American vastly outnumbered by the residents of the Limburg Province of the Netherlands for whom it is an honored, revered and beautiful place. There is a waiting list for the adoption of its graves by local families. Of course it is primarily the resting place of Americans who sacrificed their lives for those who now honor them, but it is the Netherlanders’ place as much as it is ours. It came from their farmland, used their labor, was initially dedicated with flowers and flora brought in the truckloads from all of south Netherlands, and has received their continuing care. And for many of them, the story of the African Americans who came to be among them at a very difficult time in 1944-1945 is vital and important. It’s a history that should not be scrubbed away, or taken down and placed in storage.

Chris Dickon - February 2026

Notes

1. https://www.newsweek.com/memorial-to-black-us-soldiers-who-died-in-ww2-quietly-removed-11020241

2. https://blackliberators.nl/en/about

6. https://www.robertedsel.com/post/time-will-not-dim-the-glory-of-their-deeds

7. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/11-4.pdf, p. 36 ff.

Note: The Employment of Negro Troops by Ulysses Lee was a 750 page document produced for the Center of Military History of the U.S. Army over the years 1947-1951.

9. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/11-4.pdf, p. 38

10. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/11-4.pdfp. 111

11. https://www.history.com/articles/black-soldiers-burials-netherlands

also

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012916378&seq=7

Crosses in the Wind is the definitive narration of the creation of the Margraten Cemetery, written by Captain Joseph Shomon, commander of the 960thQuartermaster Service Company.

13. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9981

14. https://www.newstimes.com/local/article/jefferson-wiggins-remembered-for-his-courage-4183600.php

also

Jefferson Wiggins was a nineteen-year-old enlisted man, put in leadership of the day-to-day work of the digging and burials of Margraten by Captain James Shomon.

16. Samuel deKorte’s blog contains links to extensive international reporting.

17. Kirkels, Mieke and Dickon, Chris Dutch Children of African American Liberators. McFarland Publications, 2020, p. 70.

18. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012916378&seq=7, p. 67.

19. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birth_of_a_Nation

20. http://hhc.hplct.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/WWI_Reader_Race-and-WWI.pdf , p. 33

21. Wynn, Neil A. The African American Experience During World War II, Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, p. 5

22. https://archive.org/details/unknownsoldiersb00barb/page/132/mode/2up

As an example, a letter from American officials to French mayors asked that they move to prevent relationships between African American soldiers and French women. “The question is of great importance to the French people and even more so to the American towns, the population of which will be affected later when the troops return to the United States. It therefore becomes necessary for both the colored and white races that undue mixing of these two be circumspectly prevented.”

23. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/11-4.pdf p. 140

24. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/11-4.pdf p.689 ff.

Also.

Kirkels, Mieke and Dickon, Chris Dutch Children of African American Liberators. McFarland Publications, 2020, p. 84

25. Reynolds, David Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, Harper Collins, 1995 p.219

27.

Copyright © 2026Chris Dickon - All Rights Reserved.